Former Pentagon strategist Phillip Karber, whose Georgetown students shockingly — and wrongly — concluded that China was hiding thousands of nuclear warheads.| Estonian Foreign Ministry/Flickr This is the radical new world of open-source intelligence — where crises move faster, information is everywhere and anyone can play.Intelligence isn’t just for governments anymore, thanks to three major trends over the past several years: the proliferation of commercial satellites, the explosion of Internet connectivity and open-source information available online, and advances in automated analytics like machine learning.These changes have touched every part of the intelligence landscape.In particular, they’ve given rise to a host of non-governmental detectives who track some of the most serious and secret dangers of all: nuclear weapons.

Former Pentagon strategist Phillip Karber, whose Georgetown students shockingly — and wrongly — concluded that China was hiding thousands of nuclear warheads.| Estonian Foreign Ministry/Flickr This is the radical new world of open-source intelligence — where crises move faster, information is everywhere and anyone can play.Intelligence isn’t just for governments anymore, thanks to three major trends over the past several years: the proliferation of commercial satellites, the explosion of Internet connectivity and open-source information available online, and advances in automated analytics like machine learning.These changes have touched every part of the intelligence landscape.In particular, they’ve given rise to a host of non-governmental detectives who track some of the most serious and secret dangers of all: nuclear weapons.

The world of open-source nuclear sleuthing is wide open to anyone with an Internet connection.It draws people with a grab bag of backgrounds, capabilities, motives and incentives — from hobbyists to physicists, truth seekers to conspiracy peddlers, profiteers, volunteers and everyone in between.Many are former government officials with years in the field, but others are amateurs with little or no experience.

There are no formal training programs, ethical guidelines or quality control processes.

And errors can go viral; nobody loses their job for making a mistake.

The open-source revolution has been lauded for disrupting and democratizing the secretive world of intelligence.There is no doubt that open-source intelligence is invaluable and that spy agencies must find new ways of harnessing its insights.But the news is not all good.Citizen-detectives also generate risks.

From the most obvious risk of getting it wrong, to harder-to-see downsides like derailing diplomatic negotiations by publicly revealing sensitive findings, the U.S.intelligence community needs to pay attention to the potential dangers of open-source intelligence as it adapts its spycraft to the digital age.

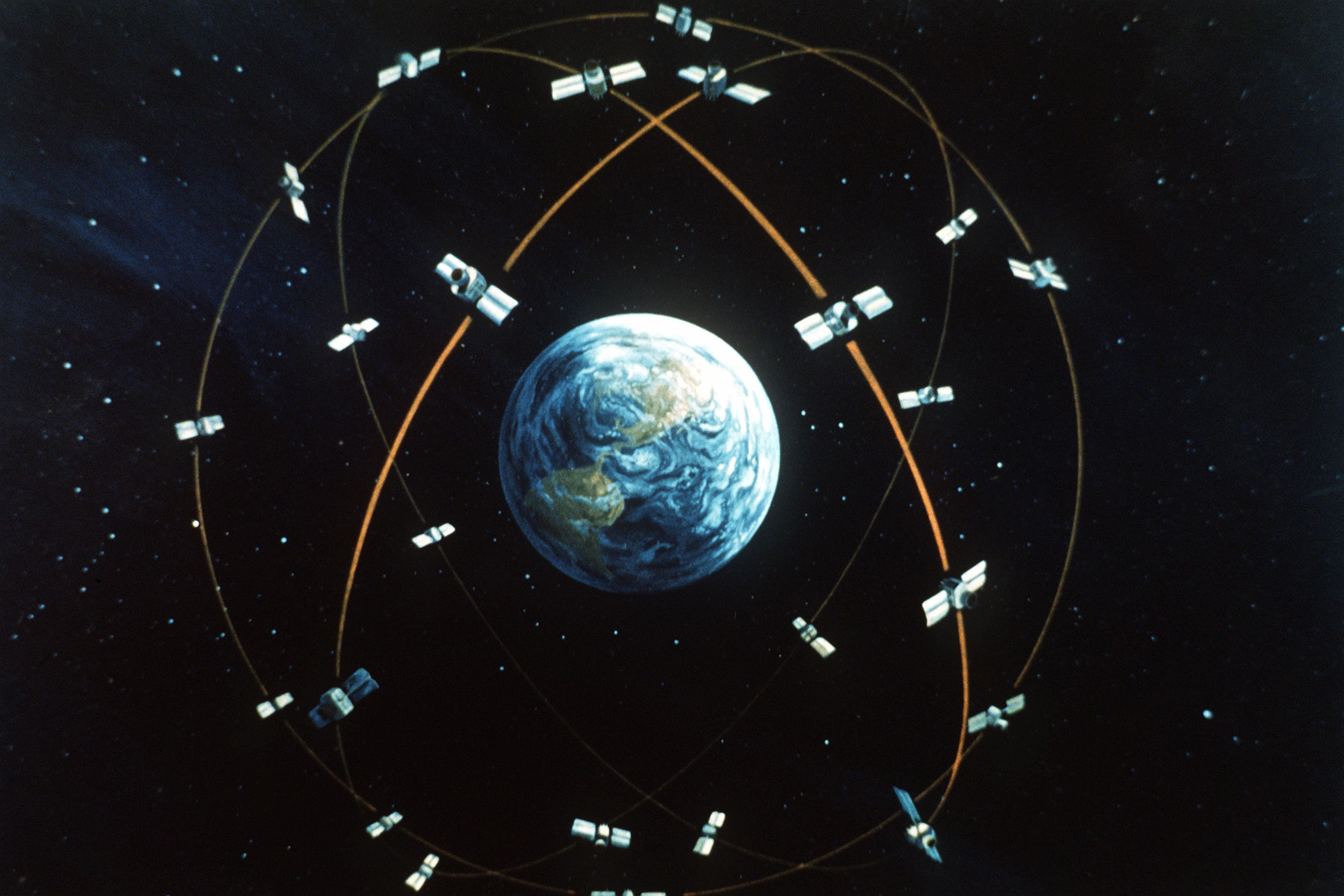

Tracking nuclear threats used to be a superpower business, because much of it was done from space and governments were the only ones with the know-how and money to build sophisticated satellites.Today, the commercial satellite industry offers low-cost eyes in the sky to anyone who wants them.Already, 3,000 active satellites orbit the earth; according to some estimates, by 2030, there will be 100,000.

While spy satellites still have greater technical capabilities, commercial satellites are narrowing the gap, with resolutions that have improved 900 percent from just 15 years ago.And more satellites mean the same location can be viewed multiple times a day to detect small changes over time, giving a dynamic view of unfolding threats.

Connectivity is changing the spy business, too, turning everyday citizens into intelligence producers, collectors and analysts — whether they know it or not.Each day, millions of people photograph and videotape the world around them to share online.Apps track all sorts of data, including the bars we visit and the places we jog .Community data sharing sites like OpenStreetMap allow users to post their GPS coordinates from their phones.These capabilities offer new clues and tools for non-governmental nuclear sleuths, who can synthesize bits of information to reveal more than anyone imagined was possible.

Technology is also transforming analysis.Downloadable 3D modeling applications make it easy for citizen-sleuths to imagine faraway places with remarkable accuracy.And increases in computing power and available data have spawned machine learning techniques that can analyze massive quantities of imagery or other data at machine speed.

For those analyzing nuclear threats, machine learning can help detect changes over time at known missile sites or suspect facilities.In 2017, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency asked researchers at the University of Missouri to develop machine learning tools to see how fast and accurately they could identify surface-to-air missile sites over a huge area in Southwest China.The team developed a deep learning neural network (essentially, a collection of algorithms working together) and used only commercially available satellite imagery with 1-meter resolution.Both the computer and the human team correctly identified 90 percent of the missile sites.But the computer completed the job 80 times faster than humans, taking just 42 minutes to scan an area of approximately 90,000 square kilometers (about three-quarters the size of North Korea).

All of these developments have given rise to an ecosystem of nuclear sleuths that looks very different from the classified world of intelligence agencies.Open-source researchers include academic experts and employees of large multinational corporations that do business around the globe or smaller firms that operate satellites.

Others are just private individuals who enjoy scouring the web and sharing their findings with like-minded hobbyists.And some intend to deceive.

This is the Wild West compared to the classified world.In spy agencies, participation requires security clearances and adherence to strict government policies.Analysts come with narrower backgrounds but higher average skill levels.They work inside cumbersome bureaucracies, but have access to training and quality control.While motives in the open-source world vary, in the government the mission is generally uniform: giving policymakers decision advantage.

One ecosystem is more open, diffuse, diverse and faster-moving.The other is more closed, tailored, trained and operates much more slowly.

On the positive side, citizen-sleuths provide more hands on deck, helping intelligence officials and policymakers identify fake claims, verify treaty compliance and monitor ongoing nuclear-related activities.They can show that what looks like an ominous nuclear development by an adversarial nation is actually nothing to worry about.For example, open-source researchers demonstrated that a cylindrical foundation in Iran that might have indicated the beginnings of a nuclear reactor was actually a hotel under construction, and that an Israeli television report supposedly showing an Iranian missile launch pad big enough to send a nuclear weapon to the United States was just a massive elevator that resembled a rocket in a blurry image.

Non-governmental nuclear sleuths can also do the opposite: surface clandestine developments that might not otherwise be discovered.In 2012, my Stanford colleagues Siegfried Hecker and Frank Pabian determined the locations of North Korea’s first two nuclear tests using commercial imagery and publicly available seismological information — assessments that proved highly accurate when North Korea revealed the test locations six years later.

Another example came in July 2020 in Iran, when a fire started during the middle of the night with flames so bright, a weather satellite picked them up from space.Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization initially downplayed the fire as a mere “incident” involving an “industrial shed” under construction.

The agency even released a photo showing a scorched building with minor damage.

The photo, released by the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, of an “industrial shed” damaged by fire in July 2020.It was actually a nuclear centrifuge assembly building, and the fire was likely an explosion.| AP

Unconvinced, David Albright and Fabian Hinz, researchers at two different NGOs, began hunting.Using geolocation tools, commercial satellite imagery and other data, each separately concluded the Iranians were lying.The shed was actually a nuclear centrifuge assembly building at Natanz, Iran’s main enrichment facility.The fire was large, almost certainly produced by an explosion, and possibly the result of sabotage.

Albright and Hinz took to Twitter.By 8:00 a.m., the Associated Press was running their analysis.

By mid-afternoon, the New York Times was too.

By nightfall, as mounting evidence pointed to the possibility of Israeli sabotage, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was asked about it in a press conference.“I don’t address these issues,” he curtly replied .

The entire incident unfolded in a single day.Neither Albright nor Hinz worked in government or held security clearances.The intelligence was collected, analyzed and disseminated without anyone inside America’s sprawling spy agencies.And because it was all unclassified — the researchers didn’t have to worry about protecting intelligence sources and methods — it could be shared, drawing public attention to Iran’s cover-up and forcing questions about Israel’s role..