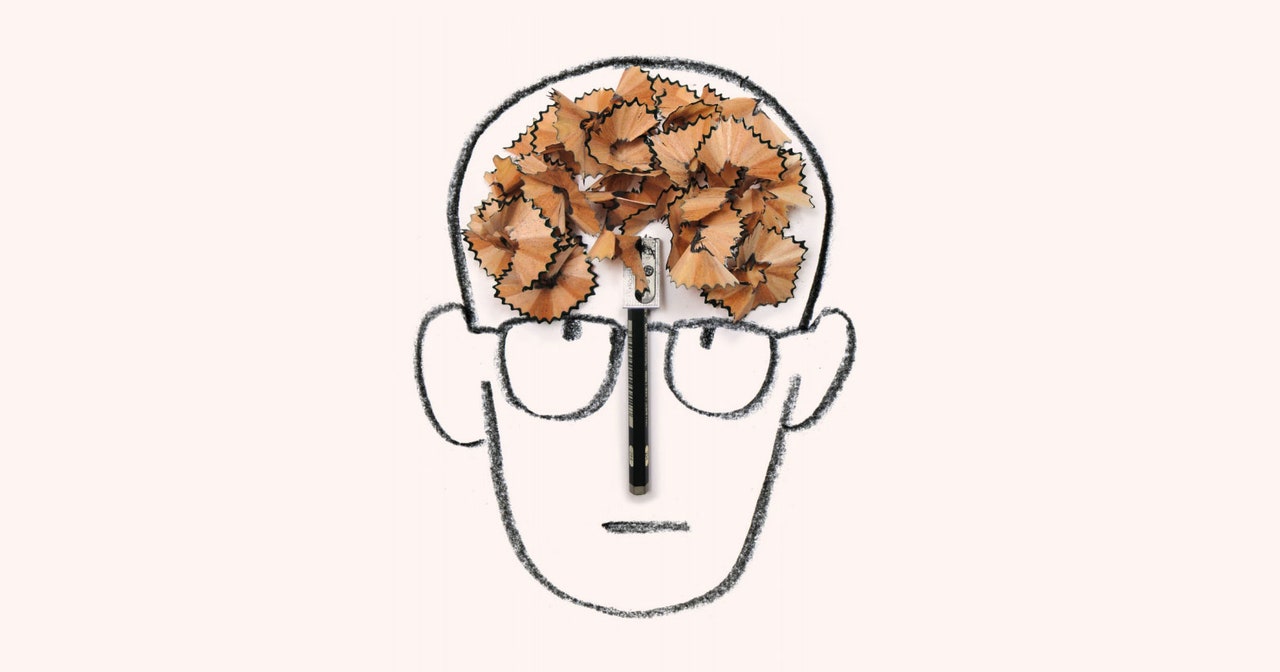

© 2016 Christoph Niemann For years, Christoph Niemann spent every Sunday conducting a drawing experiment.The artist, whose illustrations have appeared in dozens of publications, including WIRED, would sit down with a blank piece of paper and a random, everyday object.He never knew what he was going to draw—only that his drawing would include whatever object was in front of him.And so he would turn pennies into scoops of ice cream.

© 2016 Christoph Niemann For years, Christoph Niemann spent every Sunday conducting a drawing experiment.The artist, whose illustrations have appeared in dozens of publications, including WIRED, would sit down with a blank piece of paper and a random, everyday object.He never knew what he was going to draw—only that his drawing would include whatever object was in front of him.And so he would turn pennies into scoops of ice cream.

Or bananas into horse legs.Or highlighters into light sabers.

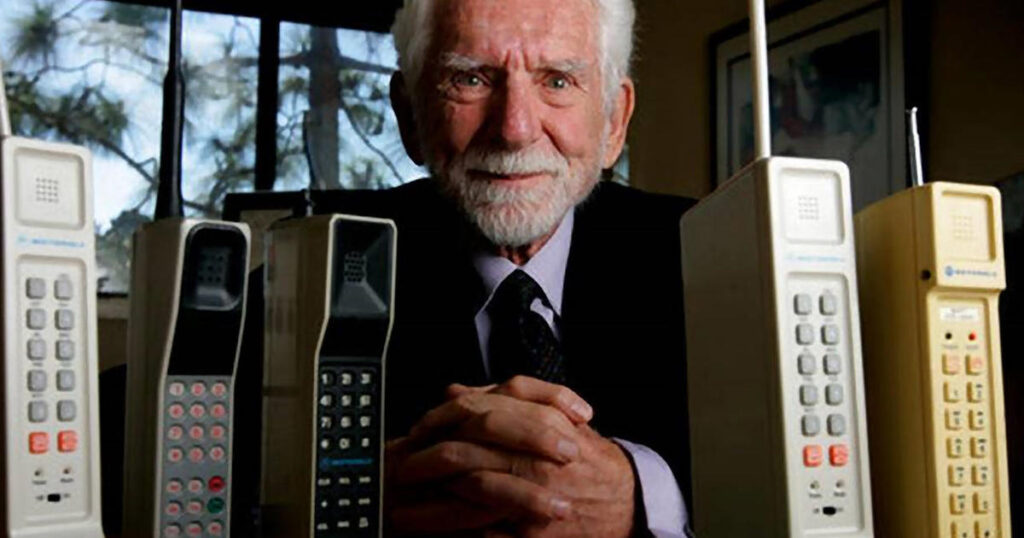

Niemann devised hundreds of these visual puns, and now he’s collected them—along with more work from his career—in his new monograph, Sunday Sketching.Published by Abrams, it’s a retrospective of Niemann’s work, but it’s also a meditation on the creative process.Throughout Sunday Sketching, Niemann uses clever drawings and his charming breed of humor to tackle tricky subjects like insecurity, money, and changing course while things are going well.The book, and the excerpt below, are a reminder that even the brightest creative minds face challenges when making consistently great work.Even in the absence of talent and inspiration, you can—through sheer practice—become so good at art that you reliably deliver very good work.Now great work—that’s something else.

For great work you also need a lot of skill and craft.But you need something else that you can’t control.Once you accept this, your life actually becomes a lot easier.

(If you are a client, please remember: All you can ask from an artist is very good work.Great work is not really plannable.) The small but distinct downside of focusing on your craft is that you become blindsided.What if I’m spending all my energy getting good at the wrong thing? Like a chef who spends night after night perfecting the burger, without realizing that everyone’s become a vegetarian.

Which leads me to the next problem …Many of the magazines that just a few years ago employed scores of art directors and fed armies of illustrators are gone, or have been reduced to a fraction of their former size.To a degree, this is a natural evolution in any industry, but the speed and swiftness with which it has destroyed businesses and radiant careers are still terrifying.

This revolution is not over.It will continue at an ever-faster pace.And there is only one thing I can do about it: Right now I’m blissfully busy, but I’m aware the party can end very quickly.The only thing I can do to make sure my work is in demand is actually focus on doing good work.This is difficult in the best of circum- stances.It gets downright impossible when you have to simultaneously worry about money.To give myself mental breathing room, I have to create a financial safety zone.

I sit down and calculate how much money I need each month (which is surprisingly consistent).I try to always have six months’ worth of expenses in the bank.If something goes terribly wrong, I know I have a few months to figure out what to do.It isn’t easy, but I found that having this buffer has real repercussions on the quality of my work, since it allows for two very critical luxuries: 1.

I can turn down assignments that might not be a good fit.2.Even though I’ve only done this once or twice in my career, I know I can afford to walk away from any job.I try to take some time once a month to inspect my accounts and see if I can just keep going or whether I have to actually freak out.

Life is not predictable, and I’m not always able to maintain this system.Worrying about money is stressful, and what’s worse, I know that this fear and desperation will show in my work.That’s why I consider financial prudence an uncool but crucial element of my practice.More interesting and more difficult are questions about the creative direction of one’s career… Being Your Harshest Critic While working, I must be kind and forgiving with my fragile self.

But sometimes I must try to look at my oeuvre with the eyes of an old and jaded misanthropic outsider (or a young and jaded misanthropic insider).Is my work just shallow pandering to an audience? Am I taking creative risks? Am I in touch with what’s happening out there? Am I blaming my audience when something falls flat? It’s hard to judge what you’re doing wrong.Even harder, to be aware of what you’re doing right.Ten years ago, I could only discuss these questions with a small set of friends and colleagues.They are still crucial when I’m facing a specific problem, but they can never look at something with the fresh eyes of somebody who’s unfamiliar with me and my work.

But now that I have social media, I can take anything—whether it’s a finished piece or a quick experiment— and see what actual readers out there think about it.I just hit a button, and in a few minutes, I have a pretty good sense of whether the world deems the idea valuable or not.Any person who claims to not be flattered when a post receives a lot of likes, or who claims to not feel the least bit insecure when a post falls flat, is lying.Like anyone whose career precedes Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, I know how it feels to work with barely any reaction from my audience.I consider social media a fascinating and maybe indispensable opportunity.

But all of those algorithms are so brilliantly designed to manipulate us with our own insecurity and vanity that it’s tempting to unconsciously equate likes and faves with quality.true measurements of creative value.Of course I’m excited if something gets a lot of response, but so do all those cat videos I’m on Instagram and Twitter.But should I also use Snapchat and Vine? When is it time to just scream “STOP! I’m ignoring all these new fads.I just want to work!”? I love stories of artists who are bolder than I am, who are not intimidated by any trends and pursue their visions with unfazed determination.

Then again, I know even more sad examples of people who have stuck to their guns.

I still remember being a student in the late 1990s and having vivid discussions with friends who doubted that designers would one day have to be able to operate computers and believed that this whole hype would quickly blow over.Being a maverick feels nice.But just because a client kills my sketch or something gets no likes on Facebook, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a masterpiece that’s ahead of its time.Maybe it’s just bad..