New numbers show an inflationary wave is still building in the U.S.economy.The labor department reports consumer prices jumped more than six percent in October as compared to a year ago — the biggest increase in 31 years.Catherine Rampell, a special correspondent for the NewsHour and columnist for The Washington Post and Lisa Desjardins have more on the numbers.

New numbers show an inflationary wave is still building in the U.S.economy.The labor department reports consumer prices jumped more than six percent in October as compared to a year ago — the biggest increase in 31 years.Catherine Rampell, a special correspondent for the NewsHour and columnist for The Washington Post and Lisa Desjardins have more on the numbers.

Read the Full Transcript

Judy Woodruff:

New numbers tonight show an inflationary wave is still building in the U.S.economy.The Labor Department reports consumer prices jumped more than 6 percent in October from a year ago.That was the biggest increase in 31 years.

Lisa Desjardins begins our coverage.

Lisa Desjardins:

Across the U.S., signs and sounds of a problem affecting millions of pocketbooks.Prices are up.

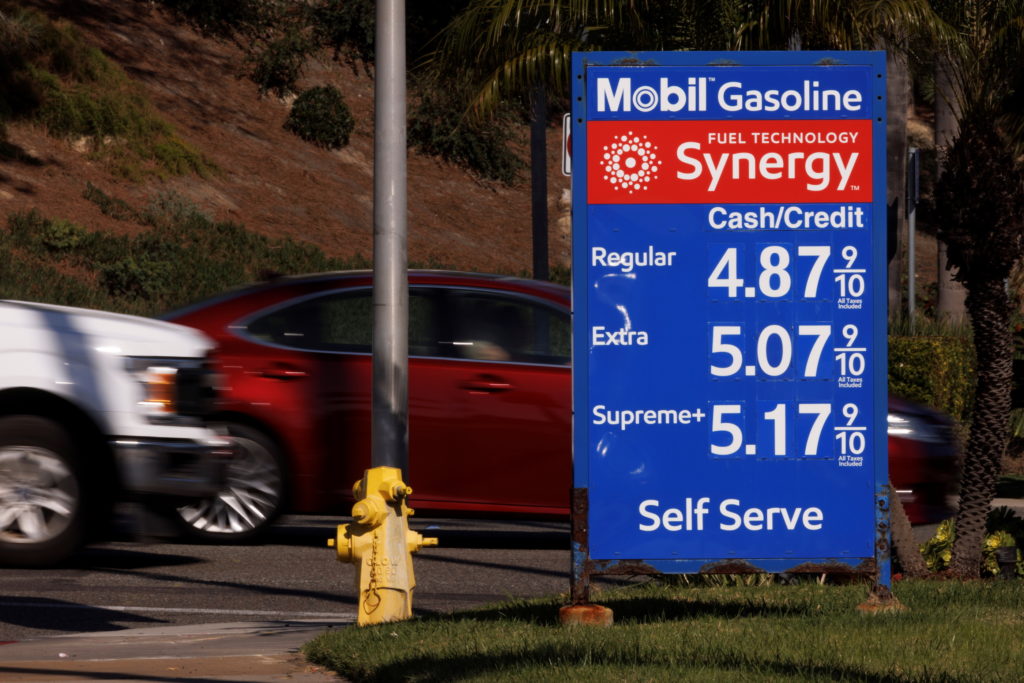

The main sectors leading the surge have big impact, gasoline and food.

Doris Knobler, Consumer:

It’s terrible.Who can afford to fill up 15, 20 gallons of gasoline? I know a lot of people are struggling.That is a heck of a lot of money.

Gabriel Bolanos, Farmer (through translator):

The prices for the seeds that I buy to produce these are also going up.That’s already hurting my business.

And, on top of that, with the gas prices, you see I have a large vehicle.I drive to markets far away.I use 10 to 20 gallons every time, and I’m a small business.It’s hard for me to earn enough money.

Lisa Desjardins:

The average gallon of gas is now in the $3 range, up more than a dollar over just one year ago, according to AAA.That’s the highest in five years.

And the pinch is even worse in some places, like in California, where pumps show prices pushing $6 a gallon and beyond.

Energy costs are fueling the national problem.In the past year, gas prices are up nearly 50 percent, and heating oil has soared 43 percent.

At the same time, some people are looking at food, and what they can afford, differently, from grocery stores.

Tracey, Shopper:

I don’t see anything going down anytime soon.But we have to eat, so you have no other choice but to pay.

Lisa Desjardins:

To food banks.

Ita Espinoza, Food Pantry Customer:

I come here because I need food for my family.You know why? Because the stores are very expensive, the food, and my money is not enough.

Lisa Desjardins:

Today, President Biden toured the Port of Baltimore, and acknowledged one source of the problem, supply chain backlogs.

Mr.Biden pledged $4 billion for construction projects at ports and elsewhere in the next two months and $3.4 billion to upgrade other trade facilities after that.

Joe Biden, President of the United States: We’re going to reduce congestion.We’re going to address repair and maintenance backlogs, deploy state-of-the-art technologies, and make our ports cleaner and more efficient.

Lisa Desjardins:

House GOP Leader Kevin McCarthy slammed the president with a blunt statement, writing: “The Joe Biden plan for increasing Americans’ standard of living is a complete failure.”

Economists and politicians disagree about how far and how long the price spikes will go, but in daily American life, inflation is firmly here.

For the “PBS NewsHour,” I’m Lisa Desjardins.

Judy Woodruff:

It is clear that this surge of inflation has already been higher and lasted longer than some had expected.

We break down more about what is happening and the potential consequences.

Catherine Rampell, who is a special correspondent for the “NewsHour” and a columnist for The Washington Post, joins me now.

Catherine, welcome back to the program.

So, it seems that prices are rising across the board, just about everywhere you look.What is behind this?

Catherine Rampell:

There are a number of factors that have been driving inflation.

The most obvious one, of course, is the pandemic.The economy powered down, during the pandemic.

It’s powering back up.There are supply chain problems all around the world, labor shortages that make it harder to find workers who can make the goods we buy, transport them, put them in warehouses, get them onto store shelves, et cetera.

So, you have shortages, which are driving up prices.And then on the other side of the calculation is the fact that Americans have a lot of money in their pockets.They have accumulated savings in this past year.It’s difficult — or it is risky, I should say, still to spend on some of the common services that consumers used to buy, things like travel or going out to eat.

So they are buying more stuff.In fact, consumers are buying more stuff today than they were before the pandemic began.So you have more demand for goods, at the same time that the pipeline through which those goods must travel is extremely fragile.

And all of that is leading to higher prices.

Judy Woodruff:

So, these explanations, Catherine, affect everything from gasoline to food to furniture.People want to improve their homes.I mean, you are saying that these causes affect every one of these things that people want to buy.

Catherine Rampell:

Right.There are shortages and bottlenecks in almost every kind of product that people want to buy right now.

And that is partly because people have money to spend, particularly here in the United States.

And it is hard to get the things that they want to spend money on.So the result of that is shortages and upward pressure on prices for the goods that are available.

Judy Woodruff:

So we know that wages are rising some.They have been rising.Are they in any way keeping up with this inflation?

Catherine Rampell:

Unfortunately, they are not.

Americans have gotten pretty big wage increases over the past year.

But they have been almost entirely — or more than entirely eaten up, I should say, by those consumer price increases.So, year over year, adjusted for inflation, wages are down, on average.

That is not adjusting for the composition of the kinds of jobs that might have been created.If you have lower-wage jobs that have been created, that might skew the overall average, of course.But other measures that do adjust for the composition of the changing work force also suggest that, on net, workers have seen their wages fall once you adjust for those higher prices.

Judy Woodruff:

The question on everyone’s mind, how long is this going to last? The Biden administration economists have been saying it’s temporary.Others agree with them.

Others don’t.

I mean, what do you see right now?

Catherine Rampell:

Well, if I knew the answer to that question, I would be a very wealthy woman.Unfortunately, we don’t know.

There’s a lot of uncertainty.I mean, there’s always uncertainty, right, with any sort of economic prediction, but especially right now, because the answer to that question is contingent on the path of the pandemic, whether various countries around the world can get adequately vaccinated and get people back to work, not just here, but in poorer countries where they don’t have adequate vaccine supply.

And that’s disrupting their economy and their supply chain there.

And it depends, of course, on consumer expectations.So there are these very real, tangible reasons that might lead to upward price pressure, things like there aren’t workers available to make the things that people want to purchase.

But there’s also sort of a fuzzier psychological aspect to all of this.How much do people expect that prices will increase? And that’s the scary part, right? As long as everybody believes that the price pressures are caused by these temporary bottlenecks, that they will be transitory, they can be transitory.

But at the point that everybody looks around and sees prices increasing and says, maybe I should preemptively raise my prices too, that’s where it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.And that’s the state of the world we don’t want to get in that the Fed is much — would be much more concerned about.

And that’s why they keep emphasizing, this is transitory, this is temporary, this is caused by the pandemic amidst other kinds of factors, and, if things get worse, we will step in before those inflation expectations get unanchored.

Judy Woodruff:

And it sounds like some of those expectations are already starting to get baked in.

But just finally, Catherine, in terms of connection to the pandemic, can we safely assume that, if the pandemic begins to lift, that inflation will get better, or not?

Catherine Rampell:

It seems like that should allay some of the pricing pressures, right?

As long as the economy can get back to where it was, in the sense that people have child care, and they can get back to work, they’re not afraid of going to work because it’s it’s unsafe for various reasons, that should allay some of these price pressures.

But that’s not the only factor.I mean, you also have a very generous set of government transfers that is also potentially giving people more purchasing power.There are — again, there’s this psychological aspect that I hope we don’t get to the point where — where everybody sort of assumes that inflation will come, more inflation will come, and, therefore, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

But that’s possible.

That’s the scary state of the world.So it’s difficult to rule that out.

Certainly, getting the pandemic more under control would be a positive for all of these trends, even if it doesn’t ultimately have the final say on ending this above-trend inflation entirely.

Judy Woodruff:

Catherine Rampell helping us understand this very tough question about inflation.

Catherine, thank you very much.

Catherine Rampell:

Thank you..